Early Hawaiian Agriculture

The early Native Hawaiian people relied heavily on agriculture and fishing, which helped to ensure an adequate supply of food and plants for sustenance. These skilled early Hawaiian farmers were very familiar with both wet land and dry land farming, as well as how to build irrigation ditches. Captain James Cook was said to have been impressed with the extensive knowledge the Native Hawaiians had on cultivation.

The Hawaiian farmer (mahi ai) was expected to produce enough food to feed the entire ohana (family). He had a vast knowledge on the types of soil in which plants would best grow, and would enrich the soil by ceremoniously placing a fish (i'a) or octopus (he'e) with the new plant. Religion played an integral role in the farmer's life, with many Hawaiian gods and goddesses being linked to certain stages of the agricultural process. All farmers prayed to the gods (akua and aumakua) for rain to help the plants grow.

Farmers were very knowledgable and understood Hawaii's unique climate and seasons, as well as the winds and rain. He would make sure to plant, weed, and harvest only at certain times, with some days being kapu (forbidden). Fitted with only a simple digging stick made of hardwood, they would also use their bodies, feet, and hands to shovel, weed, and rake. The entire ohana (family) played a roll in the food process, with each generation catering to their appropriate role.

Kalo (Taro) - A Principal Food Source

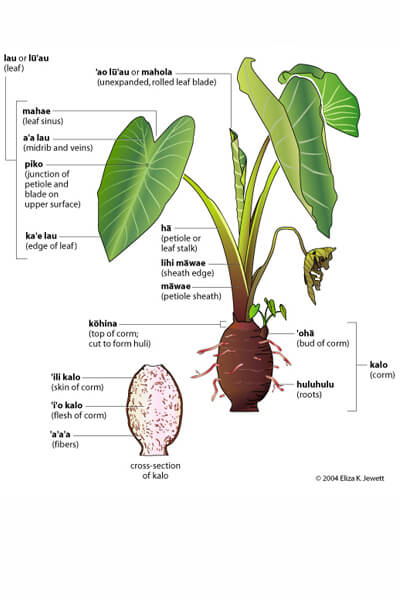

The most important (and main) crop to the Native Hawaiian's was the taro plant (kalo). Story has it that Kalo was also believed to be the first-born son of Wakea (sky father) and Hoohukuikalani (his daughter), adding to the symbolism of kalo (taro) in the Hawaiian culture. Man was said to be the second-born child, making Kalo even more important than man himself.

It is believed that when settlers arrived to the Hawaiian Islands, they brought about ten varieties of kalo from which Native Hawaiians learned how to grow over 300 varieties of kalo. Taro (kalo) is a major staple in the diets of the Polynesian people, and is the world's fourteenth most consumed vegetable. During the peak of kalo production, cultivation areas spanned more than 20,000 acres over six of the Hawaiian Islands.

Kalo plays a very important role in the culture, with the Hawaiian concept of ohana (family) having been derived from the kalo plant, or oha, which are the shoots of kalo that sprout from the main corm. Certain types of kalo were revered and only used as offerings to the Gods, while other species were only eaten by the chiefs (Ali'i).

In total, kalo takes approximately 8-12 months to mature. Hawaiians would only take as much as they needed, with farmers working together and sharing his kalo with those who were not farmers. As it was kapu (forbidden) for the men's and women's foods to be cooked together, two separate imus (underground ovens) were used. Women were not allowed to plant or cook kalo, as they were considered "unclean" due to their menstruation. The men would cultivate the kalo by cuttings called huli. Once the plant matures and the underground stem and corm (swollen plant stem) is big, the plant is harvested.

The corm of the kalo plant is cooked in an imu, then is peeled and eaten or pounded into a thick paste which is mixed with water to make poi. A light purple paste, poi is commonly eaten by Native Hawaiian's, and is a prime source of starch. For long trips, cooked corm would be sliced and dried.

Kalo was often grown in irrigated patches on either mountain slopes, in valleys, or in swamps. It was also cultivated in dry land, but grows best in water. Early Hawaiians would strategically plant kalo in marshes located near the mouths of the rivers. Irrigation ditches (auwai) were developed, as well as dams. There were certain rules on how much water they were able to take from the streams, based on how hard they worked.

Like other plants in its family, kalo is considered poisonous because it contains an acrid component which can be eliminated through either boiling or steaming. Poi, a Hawaiian staple, is made from the steamed, mashed corm of the karo plant, while the stems and leaves are eaten as vegetables.

To make a new taro patch, many people would gather together and generally follow this sequence:

Using a digging stick (o o), the soil would be dug up.

Using the soil, they would build walls or banks around the kalo patch.

Using the end of a coconut fronds (ku au niu), they would pound the banks to make the earth solid, while they added leaves and grass to make the banks water tights and firm.

Water was added to the floor of the patch, and people with stamp it to make it water tight and firm.

A feast is held with an offering made to the gods.

The farmer would take his cuttings and then plant them in the mounds of soil.

The patch would then be watered.

Once the green leaves opened, the water source was taken out for two weeks.

Once the roots were set in the soil, water was then reintroduced.

The plants continued to grow in the cool running water until they were ready to be picked and eaten.

Kalo was not only used as a food source, but served a variety of purposes. Medicinally, the raw leaf stems can be rubbed on insect bites, helping to reduce pain and prevent swelling. The raw rootstock of the plant can also be rubbed on wounds to stop bleeding, while undiluted poi was applied to infected sores. Poi was also used as a pasted to help glue together pieces of tapa. The rich red juice of the poni variety of the plant was used to dye kapa (fabric), with 7 additional varieties also being used for dyes.

Following the arrival of Captain Cook in the mid to early-1800s, the cultivation and demand for kalo has dramatically decreased, due to the subsequent migration of non-Polynesians to the Hawaiian Islands. This introduction of foreigners reduced the Native Hawaiian population due to the introduction of foreign diseases. Through loss of life, the supple and demand was affected. Alternative starches such as rice were also introduced to the people, cutting the demand further.

The breaking of the kapu system after 1820 provided Hawaiians more freedom, and allowing them to eat kalo that was once strictly reserved for royalty (ali'i). It is now guesstimated that less than 400 acres of kalo are planted.

Other Polynesian Introduced Plants

Along with kalo, the Polynesians introduced a variety of plant species to Hawaii. The Native Hawaiians were able to use these plants for an array of uses other than just eating. From medicinal uses to decorative purposes, each plant was unique in its own way.

Kukui (Aleurites moluccanus) - Also known as a candlenut, its leaves are pale green, with round nuts measuring 4-6 cm (1.6-2.4 in) in diameter.

Food Use:

The nuts of the plant are roasted, shelled, and pounded to make relish (inamona). Raw kernels can cause one to fall ill.

Medicinal Use:

The sap of the plant speeds up the healing of skin wounds. For children with thrush, the sap of the green fruit would be rubbed in the mouth. Leaves were known to help with swelling and infection when applied as a poultice.

Fishing Use:

If hau wood was unavailable, wooden floats would be made of kukui wood.

Illumination:

Also refereed to as candlenuts, the kernels of nuts were valued for their quality and the quantity of oil, and were used for illumination purposes. Kernels would be strung together and wrapped in dried ti leaves, with bamboo handles, to create a large torch. Small torches, candles, and stone lamps were also fashioned with the oil from its nuts.

Dye / Stain Use:

The soot from burned nuts was used for painting the canoes hulls, kapa, and for tattooing. The inner bark, when pounded with water, makes a red-brown stain used to due fishing nets and kapa. The oil from the kernels was also applied to surfboards during the finishing process

Mai'a (Musa paradisiaca) - Also known as a banana plant, which produces bananas and plantains.

Food Use:

Mashed bananas were used as a poi when taro was scarce. The fruit of the plant was eaten cooked or raw, depending on the variety.

Medicinal Use:

The honey secretion from the tips of the flowers were given to babies as vitamins. The roots of certain varieties were also used for thrush.

Dye / Stain Use:

The juice of the buds were used to create a dye.

Religious Use:

The leaves of the plant were used to cover small shrines, with the fruit also being offered to the gods. The leaves were also used ceremoniously to wrap the bodies of the kings.

Recreational Use:

The trunk of the tree was used to transport canoes by rolling on top of the trunk. The trunk was also used as a target for spear throwing.

Uala (Ipomea batatas) - Also known as a Hawaiian Sweet Potato. God of sweet potato was Kamapua'a.

Food Use:

Tubers were baked in an imu (oven) and eaten. When baked, peeled, mashed, and mixed with water, poi would be made. A dessert using grated tubers and coconut milk would be made and baked for dessert.

Medicinal Use:

Tubers were used to induce vomiting, and as a laxative. When gargled, it also helps to clear phlegm from the throat.

Household Use:

Dried leaves and old vines were used as padding to be used under floor mats.

Animal Use:

Hogs were fed tubers that were deemed inferior, as for the final fattening.

Hau (Hibiscus tiliaceus) - Shrublike with thick green leaves and curved branches.

Medicinal Use:

The slimy sap at the base of the flower, under the bark, is a mild laxative which is also given to woman during childbirth to help with the delivery of the baby.

Construction Use:

The curved branches of the plant have been used for outrigger booms and outrigger floats, in the event that the wood of the wiliwili was unavailable. The smaller branches were also put to use for spears for practice, kite frames, plows, floats for fish nets, and as handles.

Cordage:

The inner bark of the hau was braided and twisted for cordage, which was used for various things, such as;

sandals

fishing nets

ropes

strings for the bow

slings

Hala (Pandanus odoratissimus) - There are male and female versions of the hala tree, with the female producing an 8-inch pineapple at the center of the fronds. The pollen of male leaves is used as a love "charm" and talcum.

Food Use:

Normally eaten only in a time of famine, with the fruit of the plant being cut when near-ripe, used to make leis.

Medicinal Use:

The aerial roots of the plant could be cooked or eaten raw.

Leaf Use:

Leaves could be woven together to to make;

hats

fans

canoe sails

mats

kites

pillows

baskets

sandals

thatch roofing

Trunk Use:

The trunk of the hala tree is very hard to the core, making it ideal for posts or the ukeke (stringed Hawaiian instrument / bow).

Olona (Touchardia latifolia) - A flowering shrub. Unlike its mainland cousins, it does not have stinging hairs.

Cordage:

The inner bark of the olona was braided and twisted for cordage, which was used for various things, such as;

fishing nets

fishing lines

nets (for carrying purposes)

net base for capes, cloaks, and helmets

Wauke (Broussonetia papyrifera) - This flowering plant is a shrub or tree which grows 10 to 20 meters tall (having reached up to 35 meters tall).

Cloth:

The inner bark of the Wauke was known to produce the finest, softest, most durable kapa (fabric) known. The fabric was also washable.

Olena (Curcuma domestica) - More commonly known as tumeric.

Medicinal Use:

Roots were crushed, then dropped into the ear to relieve an earache, or into the nostrils to relieve sinus cavities.

Dye / Stain Use:

Juice from the raw roots of the Olena was used to make yellow dye. The root, when cooked, would create a deep orange dye.

Ulu (Artocarpus altilis) - Also commonly known as Breadfruit.

Food Use:

The fruit was baked in the imu (oven), pounded in to poi, and used for pudding. Pigs were also fed the fruit to fatten them up.

Medicinal Use:

The milky sap of the plant was used as latex and chewing gum.

Latex used for some skin diseases.

Dye / Stain Use:

The flower of young males creates a tan dye, while the flower of older males makes a brown dye.

Trunk Use:

The trunks of the ulu were used for surfboards (due to the lightness of the wood), for drums, poi boards, canoe boats, etc.

Ko (Saccharum officinarum) - Most commonly known as sugarcane.

Food Use:

The stalk of the ko plant was chewed on for energy. The juice was also fed to babies, and to sweeten puddings like kulolo and haupia.

Medicinal Use:

Chewed on after taking medicine, and used as a sweetener.

Leaf Use:

Leaves were used as a covering for the inside of walls, or to thatch shelters in the event that pili grass was scarce.

Pia (Tacca leontopetaloides) - Known for its fine, nutritious starch, extracted from the round tuber.

Food Use:

Mixed with coconut milk which is wrapped in ti leaves, and steamed in an imu (oven), to make haupia, a delicacy introduced by the Tahitians.

Cooking Methods of the Early Hawaiians

Native Hawaiians relied on an imu, or earth oven, to prepare a wide variety of hot meals. The 2-4 foot deep (61-122 cm) lua, or round pit, was dug into the earth as to specifically accommodate for the amount of food being prepared. Green plant material was needed to create steam. Native Hawaiians utilized a variety of plants, such as banana leaves, ti leaves, honohono grass, and coconut palm leaf.

The imu acts as a steamer, with brown or gray porous and dry lava rocks lining the bottom of the hole (Blue basalt rock is not included). Firewood is then placed on the rocks, which is then covered with imu stones, another porous rock. The rocks would then be heated until they were red hot, with special caution being used to ensure that wet rocks were not used if possible, as they were prone to explode and hurl shards of stone! Once the rocks were to the correct temperature, wet banana leaves and ti leaves would be placed on the rocks to provide protection for the food, as well as steam for cooking. Once in place, food would then be placed in the imu, where it is then covered with more leaves, lauhala matting (or burlap bags used in modern days), and then dirt.

Hawaiian Cooking Methods -

Ko ala - To broil meat or fish over coals

Kunu - To broil meat or fish over coals

Pulehu - To cook using hot embers (breadfruit, bananas, and sweet potatoes were often prepared using this method)

Palaha - To broil meat over coals

Lawalu - To broil food which was wrapped in ti leaves over coals

Hakui - To steam vegetables, fish, or meat, by placing hot stones in water

Pu holo - To steam the meat of larger animals, such as pig, through the use of hot rocks which were stuffed in the flesh in a sealed calabash.

Common Dishes, Utensils, and Cooking Materials of the Hawaiians

Apu - Cups made of small gourds or coconut shells

Lau mai'a (banana leaves) - Used as serving dishes

Lau niu (Coconut leaves) - Woven in to trays

Hue wai - Water gords

Ipu holoi lima - Finger bowls

Ki 'o 'e palau - Coconut shells used as small scoops

Pa - A platter made of milo, kou, or kamani wood

Pahi - Knives made of sharks teeth, stone flakes, or bamboo

Pohaku ku'i - Stone pounders

Papa ku'i 'ai - Poi pounding board

Wa'u - Scrapers made out of shell to remove skin

Umeke - Bowl made of milo, kou, or kamani wood

Animal Proteins Eaten by Native Hawaiians

Native Hawaiians also relied on the meat of pigs, dogs, and birds for protein. Pigs (pua'a) were a major staple and would be bred in large numbers, as the meat would be used for feasts and religious offerings. When a pig was killed, the Hawaiians would remove the organs and singe off the hair by rubbing the pigs' carcass over hot rocks. One of the traditional Hawaiian feast staples is kalua pig, which is salted and slow cooked in the imu for 2-4 hours. Dogs (ilio) were also a common meat eaten at feasts, and was the preferred meat of the Hawaiians. Birds, such as chicken and wild birds, were also eaten. Chickens then resembled the fighting cocks of today, and their eggs were not eaten by the people, but incubated by the hen. Chicken was cleaned and wrapped in ti leaves, then soaked in coconut cream. Native Hawaiians also considered 32 Native Hawaiian birds to be edible!

Food & the Kapu System

The kapu (law) system of Hawaiians was used to control every aspect of Hawaiian life, as to maintain the normal balance and harmony of the mana (divine power). It influences all aspects of planting, gathering, cooking, preparation, and eating. The diet of men, women, and children, were controlled by the use of the kapu system, with those in violation being severely punished and or killed. It was not uncommon for offenders to have their eyeballs gouged out for even the most minor of offenses. It was kapu for women to eat any of the following foods; pork, bananas, coconut, fish, turtle, shark, tortoise, porpoise, sting ray, or whale.

It was long considered kapu for men and woman to eat together in the same room. It wasn't until Ka'ahumanu (King Kamehameha's late wife) continually pressed her step-son Liholiho (King Kamehameha II) to end the food kapu system (kapu ai). Liholiho was not overly accepting of Ka'ahumanu's proposal to end the kapu ai, however she continually pressed, along with Keopuolani (another of King Kamehameha's wives). In 1819 both Ka'ahumanu and Keopuolani convinced Liholiho to attend a symbolic feast, with both chiefs and foreigners in attendance. Turmoiled with the weight of the decision, Liholiho set sail for 2-days, complete with alcohol in tow, where he went on a 2-day drinking binge.

Upon his return to shore, Lihiliho joined the feast. Both Native Hawaiian chiefs and several other foreigners were invited, with two tables set in a European fashion, with one table being for woman and the other for men. He stammered from table to table, settling at the women's table abruptly, at which point he began to eat. It was then that those Native Hawaiian's in attendance cheered, exclaiming "Ai noa - The eating taboo is broken". It was then in 1819 that King Kamehameha II (Liholiho) ended the ai noa. He ordered that men and woman should eat together, and that woman were no longer prohibited from eating pork and other foods once deemed kapu.